By James W. Watkins, III, J.D., CFP Board Emeritus™, AWMA®

As an attorney and a fiduciary risk management consultant, my job is to protect plan sponsors, trustees, and other investment fiduciaries against unnecessary fiduciary liability…and themselves. Far too often, I find that 401(k) and 403(b) plan sponsors are their own worst enemy. As that great philosopher, Pogo, once said, “we have met the enemy, and he is us.”

I have spent the last 27+ years involved in some way or the other with fiduciary law. The one constant has been the evidence that plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries do not truly understand what their fiduciary responsibilities do, and do not, require them to do.

As a result, I am often contacted by fiduciaries with questions about fiduciary law, including requests for information on how to extricate themselves from a fiduciary-related legal predicament. As I tell my fiduciary risk management clients, the best strategy for avoiding risk is to avoid it altogether whenever possible. And that is the situation that many plan sponsors are facing with regard to deciding whether to include annuities in their 401(k) and 403(b) plans.

The two fiduciary duties most often cited in 401(k) and 403(b) litigation are the duties of prudence and loyalty

We have explained that the fiduciary duties enumerated in § 404(a)(1) have three components. The first element is a “duty of loyalty” pursuant to which “all decisions regarding an ERISA plan `must be made with an eye single to the interests of the participants and beneficiaries.’” Second, ERISA imposes a “prudent man” obligation, which is “an unwavering duty” to act both “as a prudent person would act in a similar situation” and “with single-minded devotion” to those same plan participants and beneficiaries.1

Finally, an ERISA fiduciary must “`act for the exclusive purpose‘” of providing benefits to plan beneficiaries.2 (emphasis added)

I believe in the KISS philosophy – Keep It Simple & Smart. To that end, I have a simple process that I recommend that plan sponsors use to resolve such matters. I suggest that they ask themselves these two questions:

1. Does ERISA or any other law expressly require that the investment be included in the plan?

2. Would/Could inclusion of the investment in the plan potentially expose the plan and plan sponsor to unnecessary fiduciary liability exposure?

Smart, enlightened plan sponsors will continue to refuse to offer annuities, in any form, within their plans. Why?

- With regard to annuities and the first question, neither ERISA nor any other law expressly requires plan sponsors to offer annuities or any other any specific type of investment product within a plan.

- With regard to the second question, neither ERISA nor any other law requires plan sponsors to voluntarily expose themselves to unnecessary fiduciary risk liability. Annuities present genuine fiduciary liability issues, despite the annuity industry’s ongoing refusal to acknowledge and address such issues.

Whenever there is any talk about the enactment of a true fiduciary standard to cover the financial services industry, the industry immediately threatens legal action to block such legislation, with the usual claim of seeking preservation of choice for plan participants. Advocates for a meaningful fiduciary standard typically counter by pointing out that (1) legally imprudent investment products do not constitute a meaningful “choice” for plan participants, and (2) the “choice” argument is, in reality, an attempt to cover up the fact that there are genuine questions as to whether annuities could ever qualify as a prudent investment under a true fiduciary standard. As discussed herein, the evidence suggests that due to the way that they are presently structured, few, if any, annuities could meet a true fiduciary standard

SECURE 2.0 created a “safe-harbor” from liability for plan sponsors who chose to include annuities within their plan, only to have the annuity issuer default on the payments required under the annuity. SECURE 2.0 failed to provide similar protections for plan participants who suffer losses in such circumstances.

The pro-annuity provisions of SECURE 2.0 remind me of the court’s words in Hirshberg & Norris v. SEC, where the court rejected the defendant’s suggestion that the securities laws were intended to protect the investment industry, the court stating that

[t]o accept it would be to adopt the fallacious theory that Congress enacted existing securities legislation for the protection of the broker-dealer rather than for the protection of the public. On the contrary, it has long been recognized by the federal courts that the investing and usually naive public need special protection in this specialized field.3

Replace the reference to “securities” with “ERISA” and “broker-dealers” with “annuity industry” and I believe the court’s words are equally applicable to the current situation facing plan sponsors, as annuity salesmen try to convince them to include annuities in their plans.

The annuity industry continually bemoans the fact that they cannot get more plan sponsors, and investment fiduciaries in general, to offer annuities. I talk to plan sponsors on a regular basis and the story on their reluctance to offer annuities is generally some variation of the following:

- Distrust of the annuity industry due to (1) the perceived lack of full and meaningful disclosure, and (2) the refusal of the annuity industry to acknowledge and address the genuine fiduciary liability issues that plan sponsors face due to design and overall complexity issues with annuities.

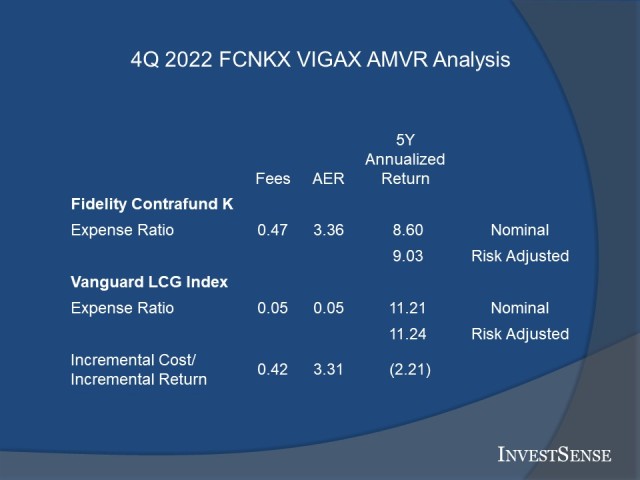

- The impact of the costs and fees typically associated with annuities, resulting in a potential breach of a plan sponsor’s duty of prudence. While annuity advocates often play a game of semantics, stating that annuities doe do charge “fees,” the reality is that annuities often have significant “costs” which are “hidden” in an annuity’s “spread.” Furthermore, such spreads, often 1-2 percent, or more, are taken prior to the annuity issuer calculating the amount of interest to be credited to the annuity owner, raising genuine potential fiduciary breach issues for plan sponsors including them in a plan.

- The difficulty and/or inability of plan sponsors to perform the legally independent investigation and evaluation of a product required by ERISA. The courts have warned plan sponsors that reliance on commissioned salespeople for advice is not legally reasonable or justifiable due to the inherent conflicts of interest in such situations.

- The frequent inclusion of certain complicated and confusing provisions within annuity contracts that protect the annuity issuer’s interests at the expense of an annuity owner’s expense, resulting in a breach of a plan sponsor’s duties of loyalty and prudence.

- The frequent inclusion of certain provisions within annuity contracts that require the annuity owner to surrender ownership and control over both the annuity contract and the accumulated value of the contract, with no guarantee of a commensurate return for the plan participant, in order for the annuity owner to receive the “guaranteed income for life” benefit. This scenario could potentially result in a windfall for the annuity issuer at the plan participant’s expense, a clear breach of a plan sponsor’s duties of loyalty and prudence.

Chris Tobe, one of my fellow co-founders on “The CommonSense 401(k) Project” has written extensively on a number of factors that generally result in annuities being a liability trap for fiduciaries. Two of the primary factors Chris cites are the single entity credit risk and illiquidity issues associated with annuities. Chris has extensive experience in the design and analysis of annuities. Plan sponsors should read Chris’ excellent analyses.

A full and complete analysis of the analysis is beyond the scope of this post. At the end of thois post I have included a list of various studies and other resources that I recommend to all of my fiduciary risk management clients. I highly recommend that plan sponsors invest the time to read these resources in order to understand the potential liability “traps” inherent in annuities.

Indexed Annuities

There are several passages in particular that I feel summarize the key legal fiduciary liability issues thatt annuities present, passages that support the distrust issues that plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries often mention to me. Equity-indexed annuities are currently a popular form of annuities. Dr. William Reichenstein is a well-respected expert in financial services. Dr. Reichenstein has authored several articles on the financial inefficiency of equity-indexed annuities. Among his findings and conclusions:

Indexed annuities (IA) including equity indexed annuities (EIAs) are complex investment contracts. (citing features such as surrender penalties; an annuity’s “spread;” arbitrary restrictions on returns that owners can actually achieve, e.g., caps and participation rates, and ability to reset same on a regular basis and on such terms at the annuity issuer desires; market value adjusted options penalizing an annuity owner who withdraws money from an annuity before term, various interest crediting methods and potential interest forfeiture rules e.g., annual reset, point-to-point, or high water point; potential interest forfeiture rules; the issue of averaging and they type of averaging used.4

More important, because of their design, index annuities must underperform returns on similar risk portfolios of Treasury’s and index funds. EIAs impose several risks that are not present in market-based investments including surrender fees and loss of return on funds withdrawn before the end of the term. This research suggests that salesmen have not satisfied and cannot satisfy SEC requirements that they perform due diligence to ensure that the indexed annuity provides competitive returns before selling them to any client.5

The interest credited on an EIA is based on the price index. So, the investor may get part of the price appreciation, but she does not receive any dividends associated with the underlying stock index. The return may be further reduced based on participation rate, spread, and cap rate. Moreover, the insurance firm almost always has the ability to adjust at its discretion the participation rate, spread, or cap rate at the beginning of each term.6

When annuity advocates questioned his findings, Reichenstein provided a follow-up paper responding to the advocates’ criticisms as follows:

I concluded that because of their structure “all indexed annuities must produce below-market, risk-adjusted returns.”7

As discussed by Reilly and Brown (2009, p. 549), to try to add value compared with a passive investment strategy, active managers use one of three generic themes: (1) market timing; (2) overweighing stocks by sectors/ industries, overweighing value or growth stocks, or overweighing stocks by size; and (3) through security selection. All attempts to beat a market index on a risk-adjusted basis use one or more of these three themes. By design, indexed annuities cannot add value with any of these themes.8

By design, (1) they do not attempt market timing, (2) they do not make sector/industry/ style/size bets, and (3) they do not try to add value through security selection. Furthermore, because hedging strategies usually require long and short positions in options contracts, the industry cannot argue that indexed annuity strategies beat the market because option values are consistently undervalued or overvalued. So, I concluded that the risk-adjusted returns on indexed annuities must trail the risk-adjusted returns available in marketable securities by the sum of their spread plus their transaction costs.9

In short, because of their design, indexed annuities cannot add value to offset their substantial embedded costs.10

In support of his argument, Reichenstein referenced a study by two-well respected members of the financial services community, Nobel laureates Eugene Fama and Kenneth French Fama and French cited the research of Dr. William F. Sharpe and the arithmetic of equilibrium accounting, declaring that

To put this argument in the context of indexed annuities, we do not need empirical tests to ensure that IAs underperform their risk-adjusted benchmark portfolio’s returns. Because their structure prevents them from adding value compared to this benchmark return, they must underperform this benchmark return by the sum of their spread plus their transaction costs.11

McCann and Luo studied equity-indexed annuities and best summarized my opinion toward equity-indexed annuities in the context of fiduciary risk management:

[The] net result of equity-indexed annuities’ complex formulas and hidden costs is that they survive as the most confiscatory investments sold to retail investors.12

Terry and Elder analyzed Reichenstein’s research and offered the findings of their own research on equity-indexed annuities.

[Reichenstein’s] essential point is that indexed annuities are simply repackaging returns that are already available to investors in the market place without adding any potential security selection or market timing value. The cost of this repackaging is the ‘spread.’ In summary, the simple economics of [equity-indexed annuities] is that investors are paying 2-3% annually in investor spreads to receive returns similar to those already available in the market, trivial insurance benefits, and to receive a no loss guarantee.13

Insurance companies [typically reserve] the option of changing many of the {index annuity’s] contract features after the first year. In particular they change the participation rates, spreads, and cap rates to maintain their investment spreads.” In other words, annuity issuers reserve the right to reduce the annuity’s owner’s return in order to maintain their investment spread.14

The opportunity costs of investing in [indexed annuities] over long horizons compared with reasonable and implementable alternative strategies are quite high….{A]t a minimum, these opportunity costs should be disclosed to potential investors at time of purchase.15

I believe the same sentiments are equally applicable to fiduciary responsibilities with regard to 401(k) and 403(b) plan and provide valuable risk management advice for plan sponsors with regard to equity-indexed annuities.

John Olson, a respected expert on annuities, provided an excellent summary on the key issues involving index annuities:

Owners of index annuities will almost never receive the full amount of gain that was realized by the index chosen. That is because there is rarely enough money left over after buying the bonds required to back the contractual guarantees to buy enough options on the index to get the full amount of any gain in that index. This is one reason why it is not true that an index annuity owner gets the upside of the market with no downside risk. At best, he or she will receive only a portion of index gain, both because the insurer could not buy enough option to get that full gain and because many index annuities limit the amount of index-linked interest that it will credit. (It does so because the specialized call options it purchases are themselves limited by a cap, allowing the insurer to purchase more upside potential than it could without such a cap.)16

Olson’s paper addresses several myth and misconception about index annuities, including Olson refuting the annuity industry’s popular “cannot lose money-no risk” claim.

It is possible–if one withdraws money from or cash (sic) in the contract during the surrender charge period. While some contracts have a genuine guarantee of principal (surrender charges my wipe out interest earned but not the money contributed in premiums) that preserves premium even in the early contract years, most do not. That said, negative performance in the chosen index or indices will not erode the contract’s cash value Thus, previously credited interest cannot be lost due to bad index performance.17

Remember the point regarding the plan sponsor’s fiduciary responsibilities on the ability to determine and analyze the interest crediting method utilized by a annuity issuer? As previously notes, the courts have warned plan sponsors that reliance on commissioned salespeople does meet the “reasonable reliance” requirement for hiring experts.

Variable Annuities

A second type of annuity sometimes appearing in 401(k) and 403(b) plans is variable annuities (VAs). I have previously written on both this blog and my “CommonSense InvestSense” blog about the potential liability issues involved with variable annuities. The “CommonSense InvestSense” blog is more directed toward on individual investors.

Over the ten-plus years that I have written the “CommonSense InvestSense” blog, one post in particular has generated the most responses, “Variable Annuities: Reading Between the Marketing Lines.” I continue to get people thanking me for an objective and plain-English explanation of an otherwise complex product. More rewarding was the fact that most people told me that the article persuaded them to avoid variable annuities altogether.

As with equity-indexed annuities, I believe that variable annuities are fiduciary liability “traps.” Interestingly enough, some insurance executives share the same concerns.

Again, a full and complete discussion and analysis is beyond the scope of this post. The purpose of this post is to hopefully raise awareness of genuine fiduciary liability issues inherent with annuities and the need for plan sponsors to consider such issues.

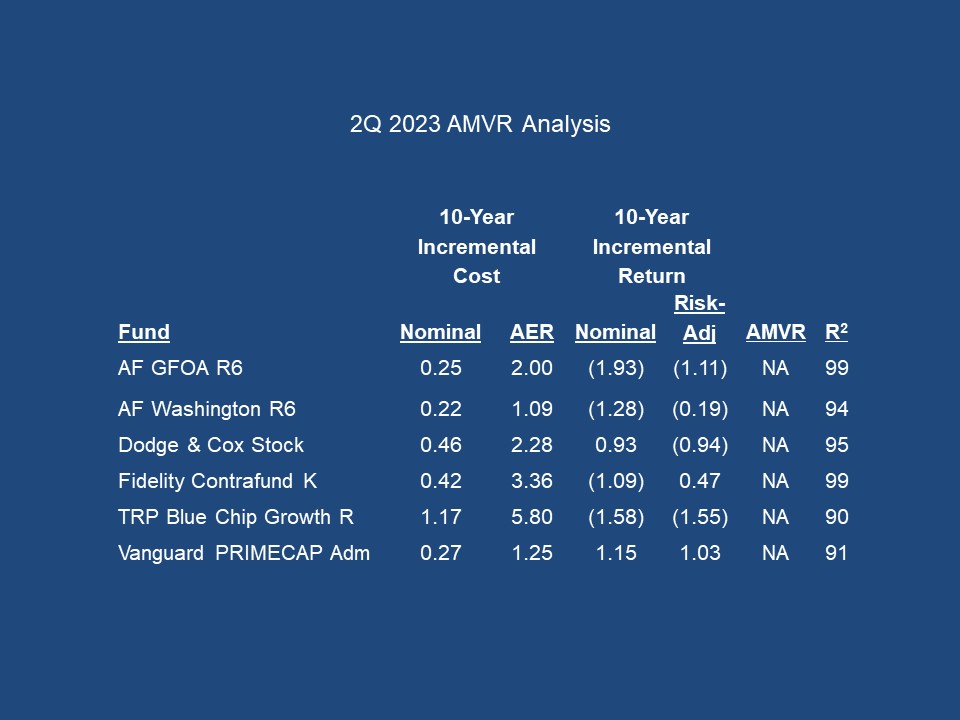

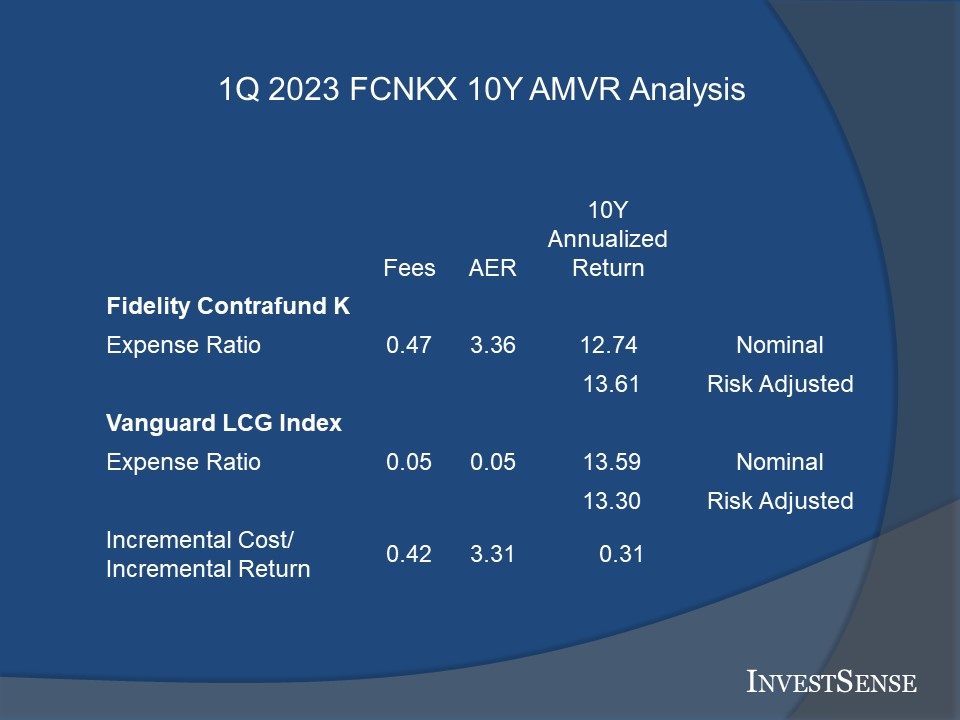

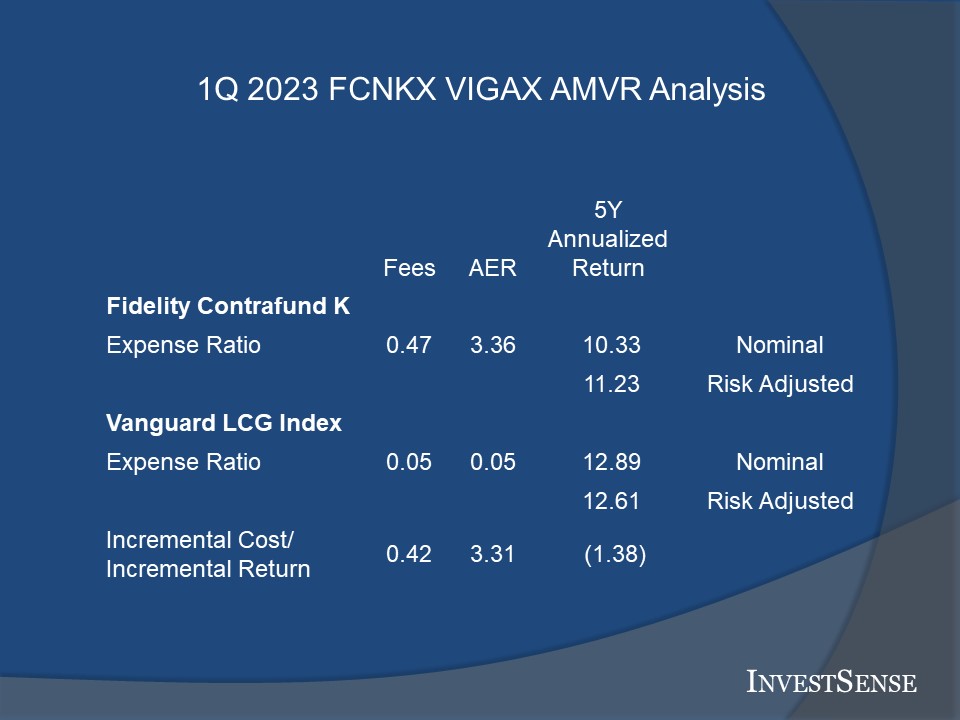

The three most concerning issues from a fiduciary liability standpoint are (1) the use of “inverse pricing” often used in calculating a VA’s annual M&E/death benefit fee, (2) the cost-inefficiency of many of the investment sub-accounts offered with the VA, and (3) the fact that equity-indexed annuities are typically structured in such a way as to promote a windfall for the annuity issuer at the annuity owner’s expense. This inequitable situation results when annuities condition the receipt of the alleged benefit, “guaranteed income for life,” on the annuity owner surrendering both the annuity contract and the accumulated value within the VA to the annuity issuer, with no guarantee that the annuity owner will receive a commensurate return.

I refer you to my “CommonSense InvestSense” blog post for a more complete analysis of the legal liability issues involved with VAs.

For this post, I just want to touch on three common sales pitches used in VA sales so that plan sponsors can recognize and avoid them.

1. Annuity owners do not pay a sales charge, so more of their money goes to work for them.

The statement that variable annuity owners pay no sales charges, while technically correct, is misleading. Variable annuity salespeople do receive a commission for each variable annuity they sell, such commission usually being a percentage of the total amount invested in the variable annuity.

While a purchaser of a variable annuity is not directly assessed a front-end sales charge or a brokerage commission, the variable annuity owner does reimburse the insurance company for the commission that was paid. The primary source of such reimbursement is through a variable annuity’s various fees and charges, particularly the M&E charge.

To ensure that the cost of commissions paid is recovered, the insurance company typically imposes surrender charges on a variable annuity owner who tries to cash out of the variable annuity before the expiration of a certain period of time. The terms of these surrender charges vary, but a typical surrender charge schedule might provide for an initial surrender charge for withdrawals during the first year, decreasing 1 percent each subsequent year thereafter until the surrender charges end. There are some surrender charge schedules that charge a flat rate over the entire surrender charge period.

2. The inherent value of the VA’s death benefit is highly questionable and often grossly excessive.

[T]he fee [for the death benefit] is included in the so-called Mortality and Expense (M&E) risk charge. The M&E risk charge is a perpetual fee that is deducted from the underlying assets in the VA, above and beyond any fund expenses that would normally be paid for the services of managed money.18

[T]he authors conclude that a simple return of premium death benefit is worth between one to ten basis points, depending on purchase age. In contrast to this number, the insurance industry is charging a median Mortality and Expense risk charge of 115 basis points, although the numbers do vary widely for different companies and policies.19

The authors conclude that a typical 50-year-old male (female) who purchases a variable annuity—with a simple return of premium guaranty—should be charged no more than 3.5 (2.0) basis points per year in exchange for this stochastic-maturity put option. In the event of a 5 percent rising-floor guaranty, the fair premium rises to 20 (11) basis points. However, Morningstar indicates that the insurance industry is charging a median M&E risk fee of 115 basis points per year, which is approximately five to ten times the most optimistic estimate of the economic value of the guaranty.20

Excessive and unnecessary costs violate the fiduciary duty of prudence. The value of a VA’s death benefit is even more questionable given the historic performance of the stock market. As a result, it is unlikely that a VA owner would ever need the death benefit. These two points have resulted in some critics of VAs to claim that a VA owner needs the death benefit like a duck needs a paddle.”

3. The “inverse pricing” method used by many VAs is inequitable.

VA advocates tout various benefits. Anyone considering a VA should also consider the question-“at what cost?” VAs often calculate a VA’s annual M&E charge/death benefit based on the accumulated value within the VA, even though contractually they typically limit their legal liability under the death benefit to the VA owner’s actual investment in the VA.

As a result, over time, it is reasonable to expect that the accumulated value within the VA will significantly exceed the VA owner’s actual investment in the VA. This method of calculating the annual M&E, known as “inverse pricing,” results in a VA issuer receiving a windfall equal to the difference in the fee collected and the VA issuer’s actual costs of covering their legal liability under the death benefit guarantee.

As mentioned earlier, fiduciary law is a combination of trust, agency, and equity law. A basic principle of equity law is that “equity abhors a windfall.” The fact that VA issuers knowingly use the inequitable inverse pricing method to benefit themselves at the VA owner’s expense results in a fiduciary breach for fiduciaries who recommend, sell or use VAs in their practices or in their pension plans.

The industry is well aware of this inequitable and counter-intuitive situation. John D. Johns, a CEO of an insurance company, addressed these issues in an article entitled “The Case for Change.”

Another issue is that the cost of these protection features is generally not based on the protection provided by the feature at any given time, but rather linked to the VA’s account value. This means the cost of the feature will increase along with the account value. So over time, as equities appreciate, these asset-based benefit charges may offer declining protection at an increasing cost. This inverse pricing phenomenon seems illogical, and arguably, benefit features structured in this fashion aren’t the most efficient way to provide desired protection to long-term VA holders. When measured in basis points, such fees may not seem to matter much. But over the long term, these charges may have a meaningful impact on an annuity’s performance.21

In other words, inverse pricing is always a breach of a fiduciary’s duties of both loyalty and prudence, as it results in a windfall for the annuity issuer at the annuity owner’s expense, a cost without any commensurate return, which also violates Section 205 of the Restatement of Contracts.

In other words, the use of inverse pricing is always a breach of a fiduciary’s duties of loyalty and prudence, as it results in a windfall for the annuity issuer at the annuity owner’s expense, a cost without a commensurate return, which also violates Section 205 of the Restatement of Contracts.

Going Forward

As shown herein, annuities have the ability to raise genuine fiduciary liability issues for plan sponsors. Those issues may become even more problematic for plan sponsors in the near future in connection with 401(k)/403(b) litigation. While some federal courts are already placing the burden of proof regarding causation of damages on plan sponsors, there is still a split in the federal courts.

There is currently a case, Matney v. Briggs Gold of North America22, which will seemingly force the legal system, most likely the Supreme Court, to establish one consistent standard for courta in 401(k)/403(b) actions. Given the fact that the First Circuit Court of Appeals and other federal circuits, the United States Solicitor General, and more recently the Department of Labor have expressed support for shifting said burden of proof to plan sponsors, the likelihood is that the Supreme Court would follow suit and rule in favor of such a policy, especially since it is consistent with the common law of trusts.

In talking with my clients about the issue of annuities in 401(k) and 403(b) plans, I ask them whether they will be able to carry the burden of proof as to causation, be able to calculate and verify the guaranteed benefits such as the interest crediting payments received within such annuities to ensure both the prudence of the products and that a plan participant’s ERISA rights are not being violated.

Similarly, will a plan sponsor be able to determine which index interest crediting model is in a plan participant’s best interests, e.g., one year annual reset, multiple year point to point, one-year monthly cap index, one-year averaged monthly? Will plan sponsors be able to determine whether the index used in such indexed annuities is legitimate and in the plan participants’ best interests? Suddenly, the simplicity of index funds is looking better and better.

Plan sponsors, and investment fiduciaries in general, need to understand the significant, and irreconcilable differences, between the insurance/ annuity industry model and the ERISA/fiduciary law model. The insurance/ annuity industry is all about managing the odds, managing risk in such a way to ensure that the odds are in their favor, that their best interests take precedence over those of their customers, that losses are offset by gains to ensure their overall profitability.

ERISA and fiduciary law is just the opposite, the focus being on equity, fundamental fairness, and certainty, always acting in such a way that the plan participant’s best interests are best served. With fiduciary law, the fiduciary gets one chance to “get it right,” there are no “mulligans” or do-overs. Furthermore, the recent SCOTU’ and Seventh Circuit Hughes23 decisions clearly establish that the concept of offsets is not recognized under ERISA/fiduciary law.

One can legitimately argue that the basic concept and structure of an annuity is the anti-thesis of fiduciary law and equitable principles. Conditioning an annuity owner’s receipt of the advertised benefits of “guaranteed income for life,” with “no investment losses,” upon the annuity owner’s surrendering both the control and ownership of both the annuity contract and the accumulated value within the annuity, without any guarantee of receiving a commensurate return, is not only fundamentally unfair and inequitable, but clearly inconsistent with both the fiduciary duty of prudence and loyalty, as it increases the odds of a windfall in favor of the annuity issuer at the annuity owner’s expense. “Equity abhors a windfall is a basic tenet of equity law, which is basic component of fiduciary law.

The typical response of annuity advocates to such criticism-that annuity owners can purchase a rider to ensure the return of their principal-does not satisfy such fiduciary law and liability concerns and only serves to further reduce the annuity’s owner’s effective end-return. Both the Department of Labor and the General Accountability Office have noted that each additional 1 percent in fees/costs reduces an investor’s end-return by approximately 17 percent over a 20-year period.24

There is a familiar expression in the investment and annuity industries-“sell the sizzle, not the steak.” That describes the marketing strategy typically used by the annuity industry, with the “guaranteed income for life” and “no risk” spiels being the “sizzle.” The inequities aspects of annuties discussed herein, inequities designed to serve the best interests of the annuity issuer, not the annuity owner, are obviously the “steak.”

Fiduciary investment risk management 101-Keep It Simple & Smart. Once again, the best strategy for avoiding unnecessary fiduciary investment risk is to avoid it altogether whenever possible. Neither ERISA nor any other law expressly requires plan sponsors to offer annuities within a 401(k) or 403(b) plan. Plan participants desiring to purchase an annuity are free to do so outside the plan, without exposing the plan sponsor to any unnecessary fiduciary liability risk.

Notes

1. Gregg v. Transportation Workers of Am. Intern, 343 F.3d 833, 841-842 (6th Cir. 2003). (Gregg)

2. Gregg, 841-842.

3. 117 F.2d 228, 233 (1949).

4. Reichenstein, W. (2009) Financial analysis of equity indexed annuities. Financial Services Review, 18, 291-311, 291 (Reichenstein I)

5. Reichenstein I, 291.

6. Reichenstein I, 298.

7. Reichenstein, W. (2011) Can annuities offer competitive returns? Journal of Financial Planning, 24, 36. (Reichenstein II)

8. Reichenstein II, 36.

9. Reichenstein II, 36.

10. Reichenstein II, 36-37.

11. Fama, E. F. & French, K. R. (2009) Why Active Investing Is a Negative Sum Game, (available at http://www.dimensional.com/famafrench/2009/06/why-active-investing-is-a-negative-sum-game.html)

12. McCann, C. & Luo, D. (2006) An Overview of Equity-Indexed Annuities. Working Paper, Securities Litigation and Consulting Group (McCain & Luo

13. Terry, A. & Elder, E. (2015) A further examination of equity-indexed annuities. 24, 411-428, 416. (Terry & Elder)

14. Terry & Elder, 419.

15. Terry & Elder, 427.

16. Olson, J. (November 2017) Index Annuities: Looking Under the Hood. Journal of Financial Services Professionals. 65-73, 71,

17. Olson, 72.

18. Milevsky, M. & Posner, S. The Titanic Option: Valuation of the Guaranteed Minimum Death Benefit in Variable Annuities and Mutual Funds, Journal of Risk and Insurance, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2009), 91-126, 92. (Milevsky & Posner)

19. Milevsky & Posner, 92.

20. Milevsky & Posner, 92.

21. Johns, J. D. (September 2004) The Case for Change, Financial Planning 158-168, 158. (Johns)

22. Matney v. Briggs Gold of North America, No. 4045 (10th Cir. 2022)

23. Hughes v. Northwestern University, No. 18-2569, March 23, 2023 (7th Cir. 2023); Hughes v. Northwestern University, 142 S.Ct. 737 (2022)

24. Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration, “Study of 401(k) Plan Fees and Expenses,” (“DOL Study) http://www.DepartmentofLabor.gov/ebsa/pdf; “Private Pensions: Changes needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees,” (GAO Study”).

Recommended Reading

Collins, P.J., Lam, H., & Stampfi, J. (2009) Equity indexed annuities: Downside protection, but at what cost? Journal of Financial Planning, 22, 48-57.

FINRA Investor Insights (2022) The Complicated Risks and Rewards of Indexed Annuties The Complicated Risks and Rewards of Indexed Annuities | FINRA.org

Fama, E. F. & French, K. R. (2009) Why Active Investing Is a Negative Sum Game, (available at http://www.dimensional.com/famafrench)

FINRA Investor Alert (2003) Variable Annuities: Beyond the Hard Sell

Frank, L., Mitchell, J. & Pfau, W. Lifetime Expected Income Breakeven Comparison Between SPIAs and Managed Portfolios, Journal of Financial Planning, April 2014, 38-47.

Katt, P. (November 2006) The Good, Bad, and Ugly of Annuities AAII Journal, 34-39.

Lewis, W. Chris. 2005. A Return-Risk Evaluation of an Indexed Annuity Investment.” Journal of Wealth Management 7, 4.

McCann, C. & Luo, D. (2006). An Overview of Equity-Indexed Annuities. Working Paper, Securities Litigation and Consulting Group.

Milevsky, M. & Posner, S. The Titanic Option: Valuation of the Guaranteed Minimum Death Benefit in Variable Annuities and Mutual Funds, Journal of Risk and Insurance, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2009), 91-126.

Olson, J. Index Annuities: Looking Under the Hood. Journal of Financial Services Professionals. 65-73 (November 2017),

Reichenstein, W. Financial analysis of equity-indexed annuities. Financial Services Review, 18 (2009) 291-311.

Reichenstein, W. (2011), Can annuities offer competitive returns? Journal of Financial Planning, 24, 36.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2008) Investor Alerts and Bulletins: Indexed Annuties SEC.gov | Updated Investor Bulletin: Indexed Annuities

Sharpe, W.F. (1991) The arithmetic of active management. Financial Analysts Journal, 47, 7-9.

Terry, A. & Elder, E. (2015) A further examination of equity-indexed annuities. 24, 411-428.

You must be logged in to post a comment.