James W. Watkins, III, J.D., CFP EmeritusTM, AWMA®

Last week I posted the following post online in X (formerly Twitter) and LinkedIn:

There is no requirement, legal, moral, or otherwise, that requires plan sponsors to offer annuities or any other type of guaranteed income products within a plan. ERISA Section 404(a) only requires that each individual investment option offered within a plan be legally prudent. Plan participants desiring annuities or other guaranteed income products are free to purchase same outside the plan, without exposing plan sponsors to unnecessary liability exposure. Plan sponsors should be asking why, with no legal duty to offer such products within a plan, the annuity industry keeps pushing for such products in-plan.

As for me, I will stand pat with the law and Einstein.

The post represented the frustration that I have with certain people in the annuity industry intentionally trying to mislead plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries by suggesting that plan sponsors have a legal, moral, or other source of obligation to their plan participants to include annuities or other guaranteed incomce products within a 401(k)/403(b). That is not only false and deceitful, but it could result in plan sponsors harming their plan participants and unnecessarily exposing the plan sponsor to fiduciary liability.

As I tell my fiduciary risk management clients, when you see a post about the alleged results of a poll suggesting that plan participants want annuities and/or some other type of guaranteed income product in their 401(k)/403(b) plan, the prudent plan sponsor’s response should “so what.” Same for when an article suggests that plan sponsors should offer such products in their plan.

For years, the annuity industry deliberately misled the courts in an attempt to persuade the courts to require that annuities be used in civil cases involving significant injuries and financial damages. The annuity industry repeatedly cited research supposedly showing that 90-95 percent of plaintiffs receiving large financial awards dissipated such awards within five years. When a court finally challenged the alleged research, the annuity admitted that no such research ever existed, that the annuity industry had simply made it up.1

As for what plan participants may or may not want as investment options in a plan, plan participants do not decide what products are offered within a plan. That is exclusively the decision of the plan sponsor.

The plan sponsor’s decisions on investment options within a plan should be based solely on the legal requirements as set out in ERISA and the associated regulations. The relevant portion of Section 404(a) states as follows:

[A] fiduciary shall discharge that person’s duties with respect to the plan….with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent person acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character and with like aims.2

Note that there is no requirement to offer any specific type of investment product within a plan. As SCOTUS stated in the Hughes v. Northwestern University decision3, ERISA only requires that each individual investment option offered within a plan be legally prudent.

ERISA’s associated regulations provide an additional warning for plan sponsors with regard to selecting investment options for a plan.

(b) Investment duties

(1) With regard to the consideration of an investment or investment course of action taken by a fiduciary of an employee benefit plan pursuant to the fiduciary’s investment duties, the requirements of [404(a)]…are satisfied if the fiduciary:(i) Has given appropriate consideration to those facts and circumstances that, given the scope of such fiduciary’s investment duties, the fiduciary knows or should know are relevant to the particular investment or investment course of action involved,…

(2) For purposes of paragraph (b)(i)…”appropriate consideration” shall include, but is not necessarily limited to:

the risk of loss and the opportunity for gain (or other return) associated with the investment course of action compared to the opportunity for gain course of action compared to the opportunity for gain (or other return) associated with reasonably available alternatives with similar risks;…4

(emphasis added)

As the courts often say, “a pure heart and an empty head” are not a defense to fiduciary imprudence.5

Fixed Annuities

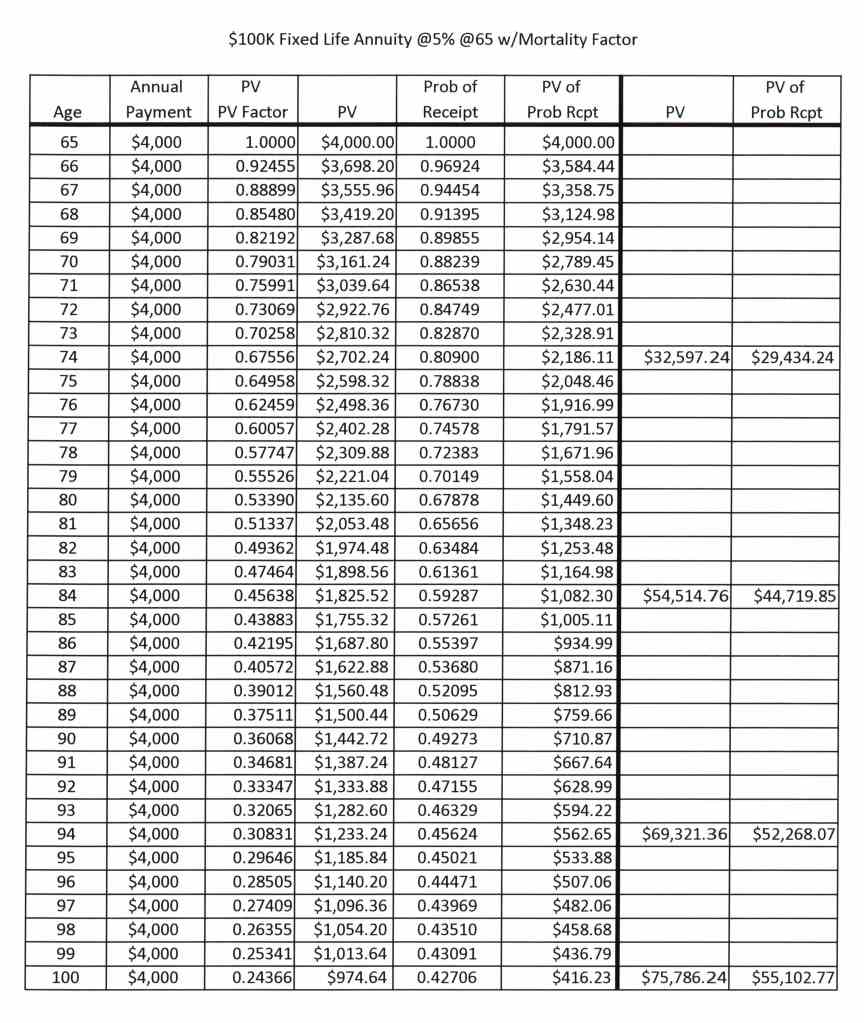

With regard to annuities, I recommend a forensic analysis appropriate for the type of annuity involved. For fixed annuities, the simplest type of prudence analysis is a breakeven analysis. A breakeven analysis evaluates the odds of an annuity owner breaking even on their investment and how long it will take.

A simple breakeven analysis can be performed using Excel’s Present Value (PV) formula. To get a more reliable breakeven analysis, both PV and mortality risk must be factored into the breakeven calculations. When both present value and mortality risk are factored in, the results typically indicate that the annuity owner would have to live well beyond the age of 100 to just break even. As a result, in terms of fiduciary prudence, it is unlikely that a fixed annuity would qualify as being prudent.

Earlier in my legal career I had to routinely perform breakeven analyses factoring in both present value and mortality risk. An example of such an analysis is shown below, based on a 65 year-old male purchasing a $100,000 single life fixed annuity with a guaranteed rate of 5 percent. As the chart indicates, at age 100, the annuity owner would be well below breaking even on his original $250,000 investment. Obviously, the results would change based on the input data used.

Variable Annuities

The issue of commensurate returns and fundamental fairness becomes an even bigger issue in terms of variable annuities and fixed indexed annuities. Here is a sampling of comments on variable annuities from investment professionals:

The authors’ main conclusion is that a simple return-of-premium death benefit is worth between one and ten basis points, depending on gender, purchase age, and asset volatility. In contrast, the median Mortality and Expense risk charge for return-of-premium variable annuities is 115 basis points. Presumably, the remaining markup can be attributed to profits, model imperfections, or, more cynically, to an implicit payment for the tax-deferral privilege.6

In a good world, variable annities wouldn’t be allowed. People don’t understand them.7

Three key fiduciary prudence issues with variable annuities are (1) the questionable value of the guaranteed death benefit, (2) the manner in which the fee for the death benefit is calculated, and (3) the cost-efficiency of the investment subaccounts offered within a variable annuity.

As for the death benefit itself, annuity expert Moshe Milevsky questioned the basic value of the benefit itself given the long-term performance of the stock market and the unlikely chance that a variable annuity owner would ever need to use the death benefit.8 As some critics have suggested, “a variable annuity owner needs the death benefit as much as a duck needs a paddle.”

The other issue with the variable annuity’s death benefit has to do with the equitability of the manner in which the fee is calculated. Variable annuities often calculate the annual fee for the death benefit on the accumulated value of the annuity, even though the typical variable annuity death benefit is limited to the annuity owner’s actual capital investment in the variable annuity. With regard to in-plan variable annuities, this strategy raises questions regarding possible violations of a fiduciary’s duty of prudence and the duty of loyalty, the obligation to act solely in the best interests of the plan participants.

With variable annuities, owners are allowed to seek market returns by investing in various subaccounts. Subaccounts are essentially the same as their mutual fund counterpart. Each subaccount charges the annuity owner a separate management fee.

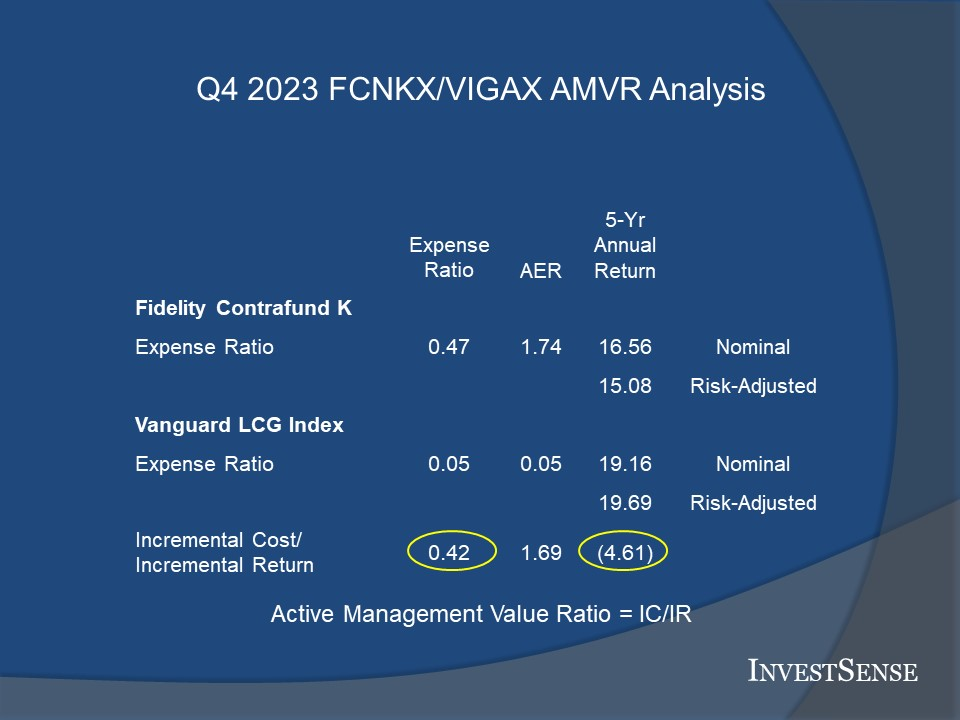

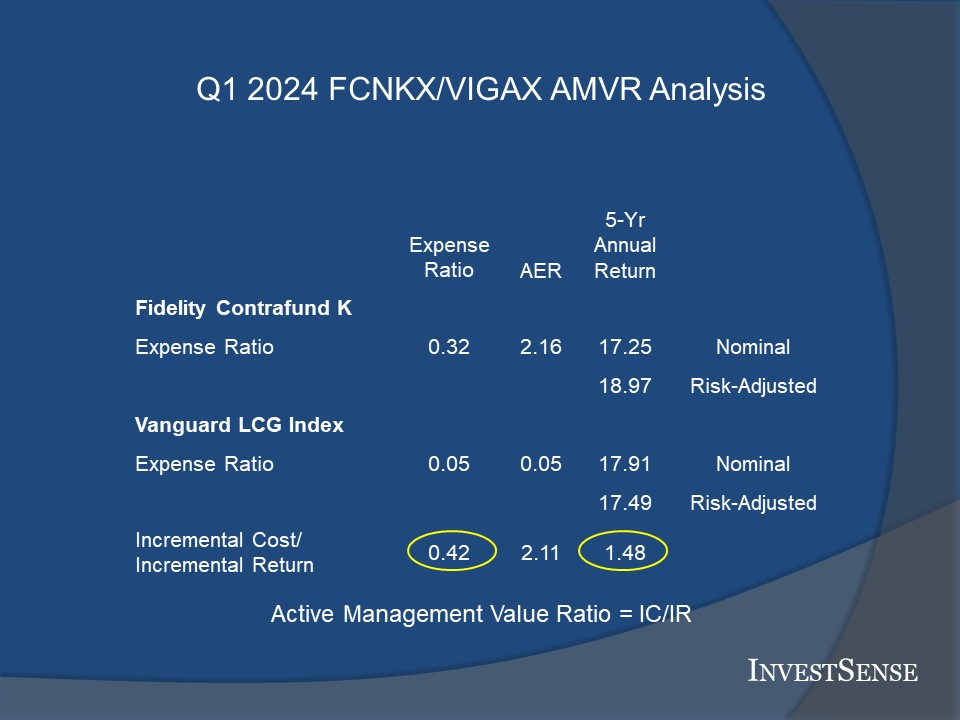

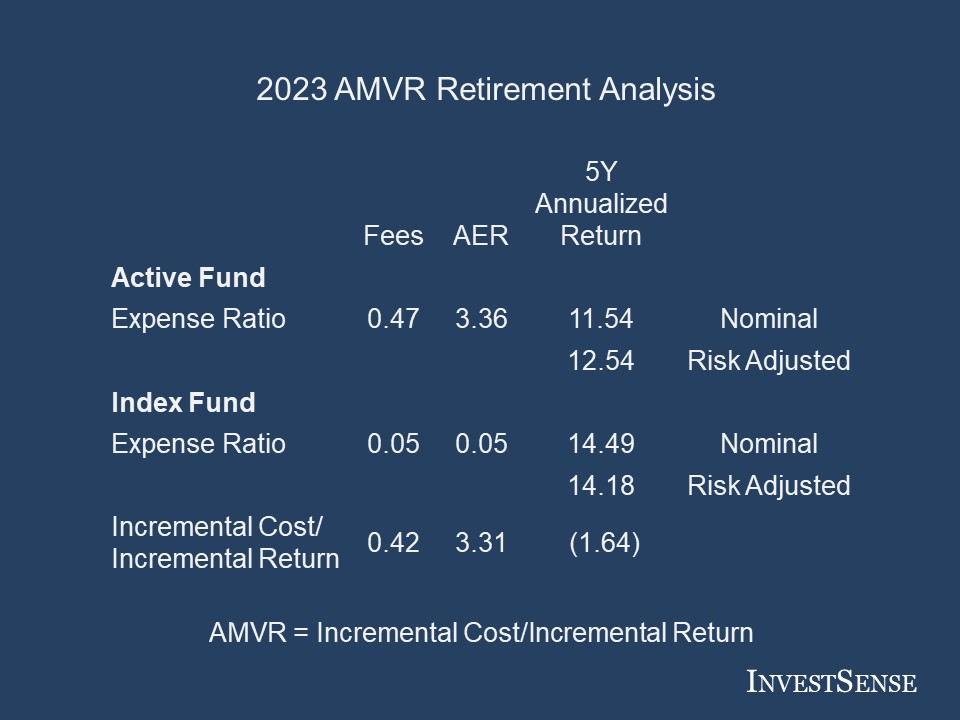

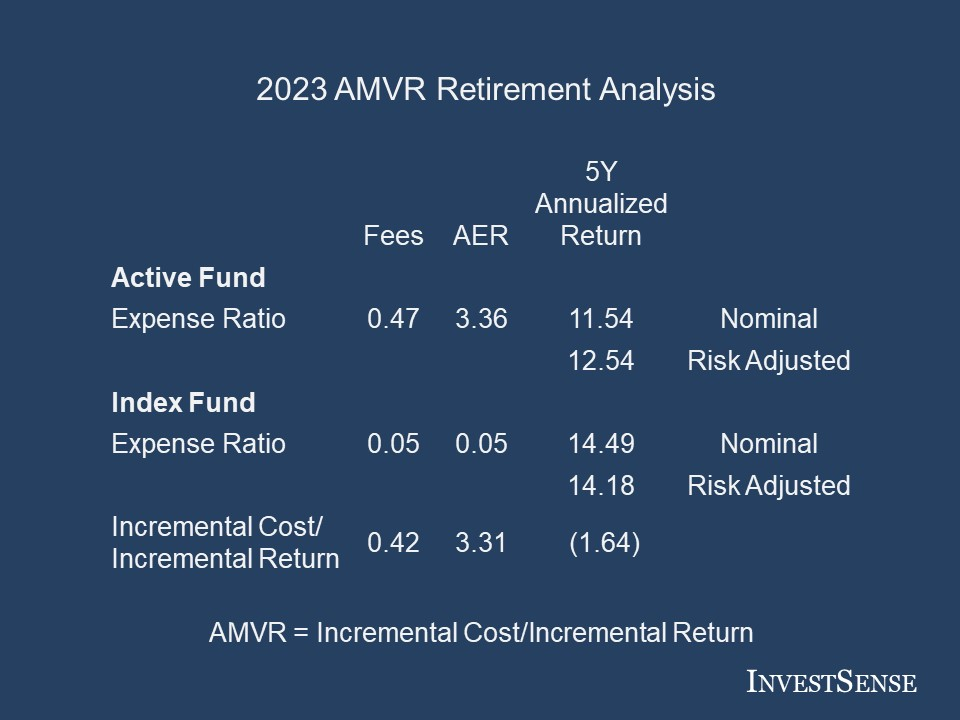

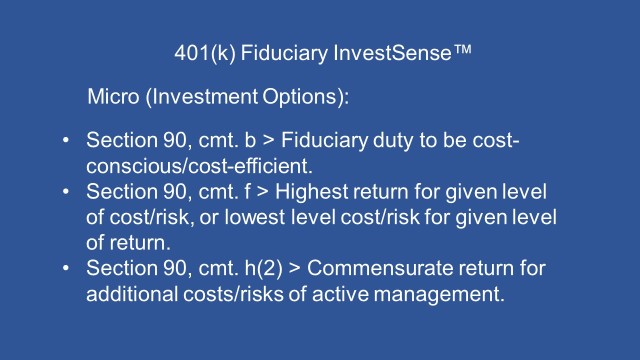

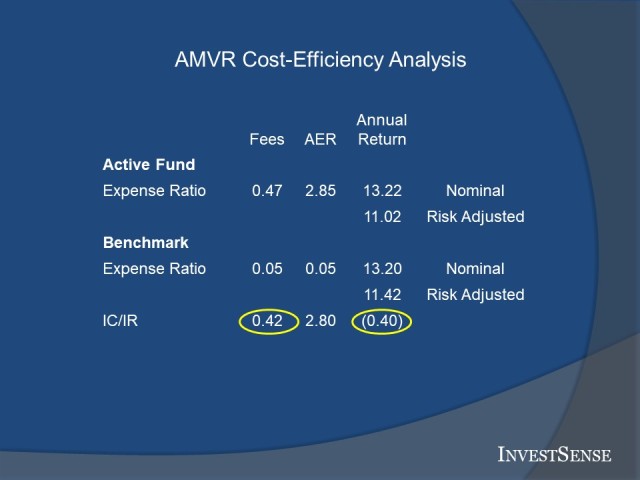

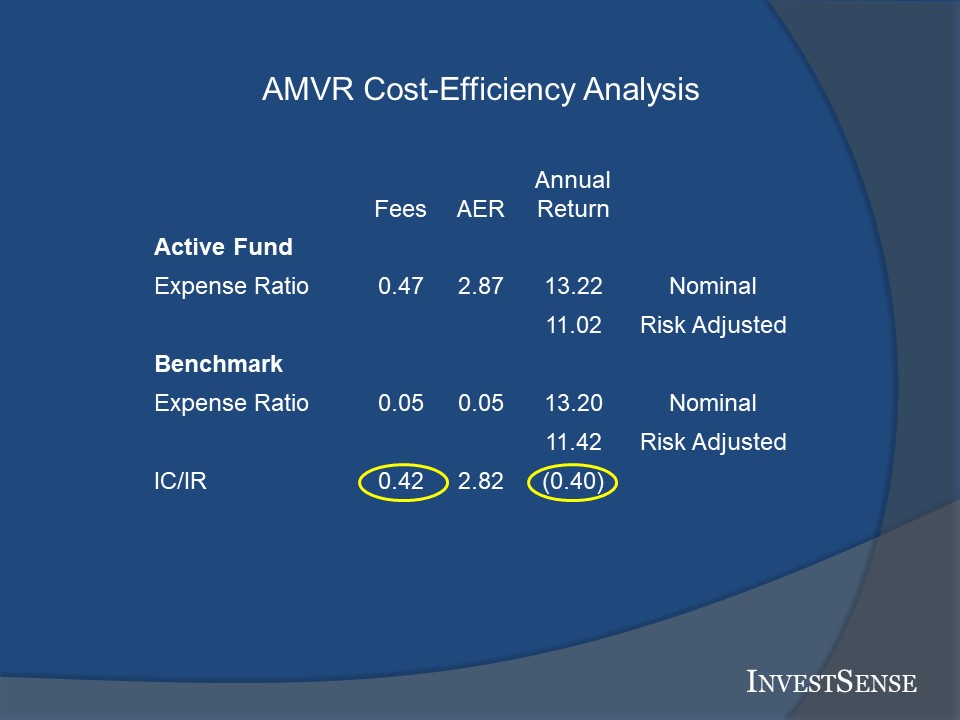

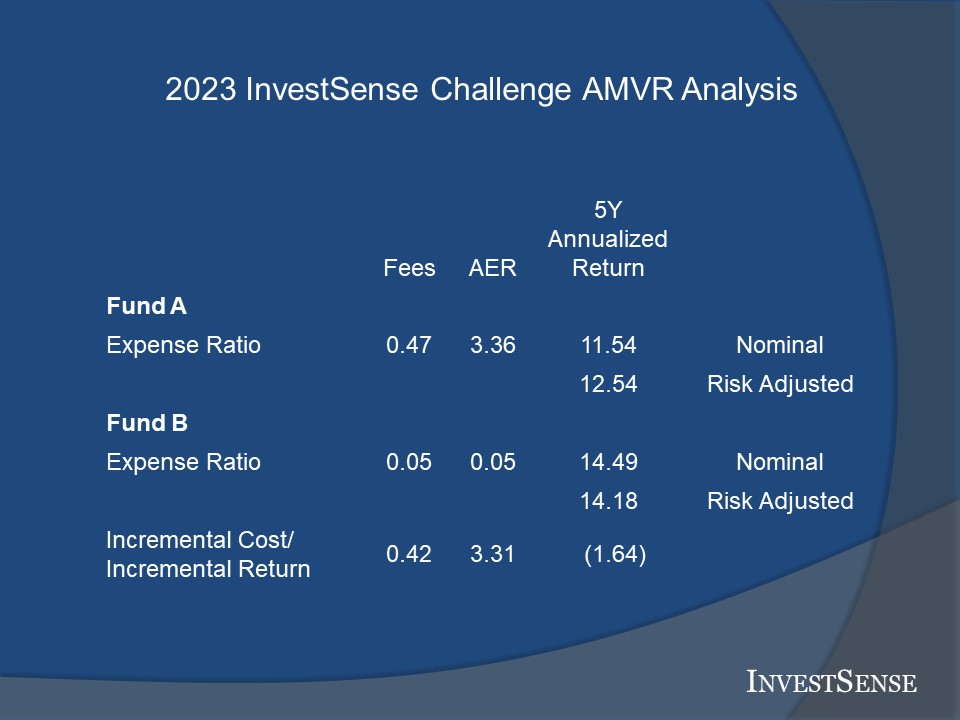

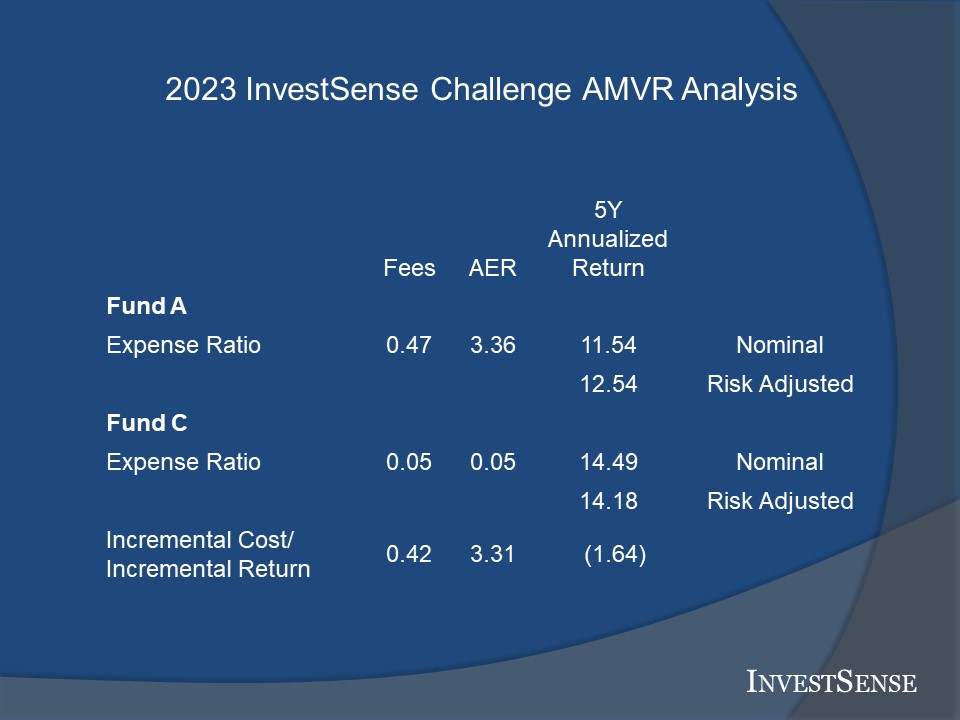

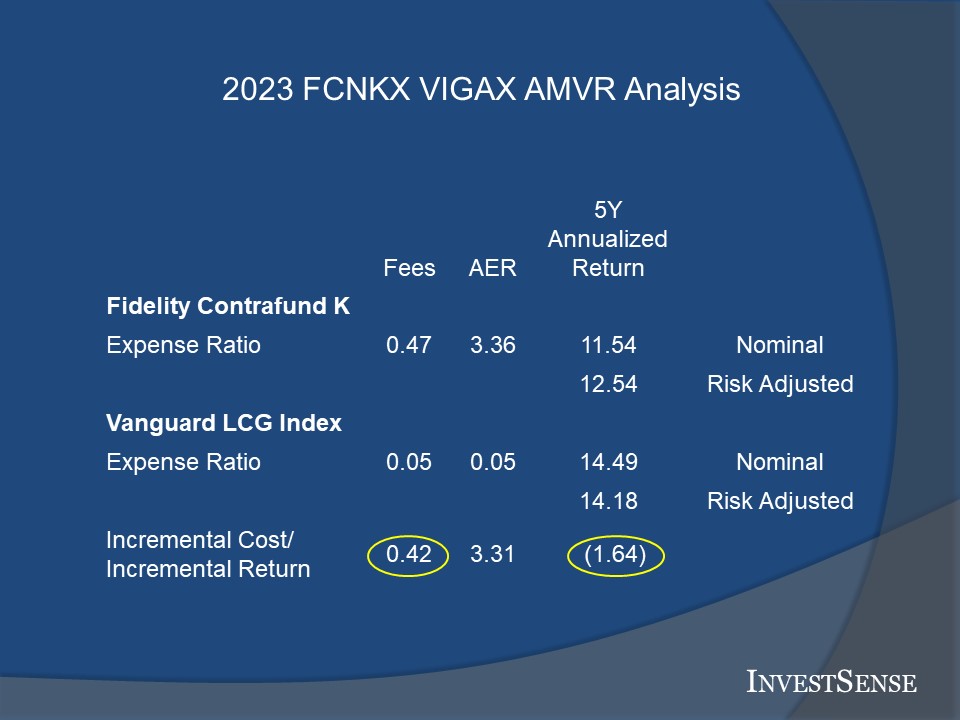

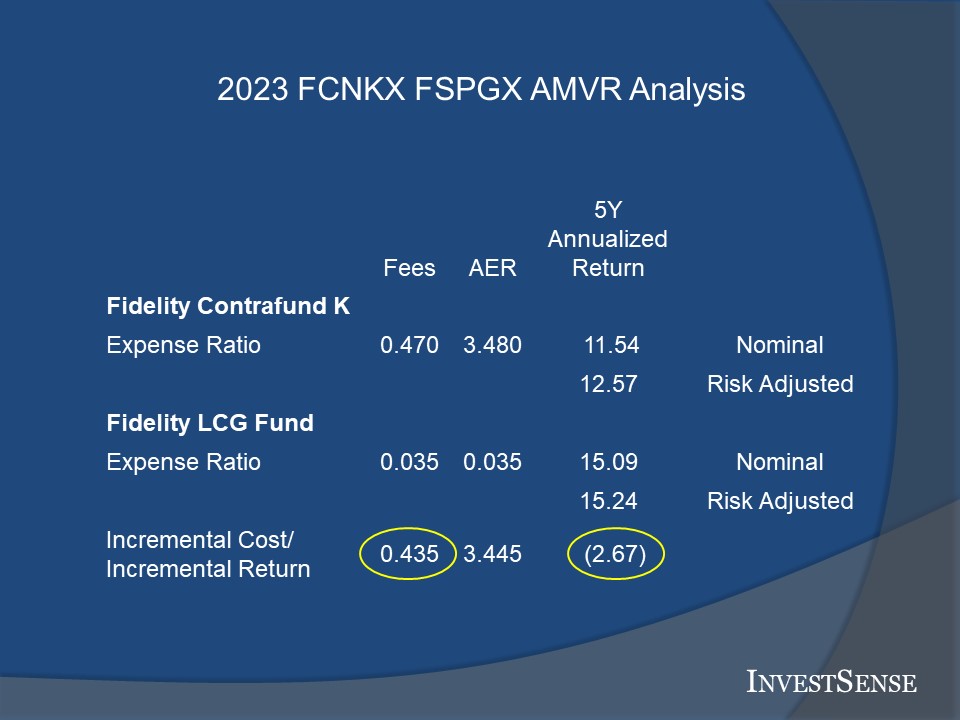

The problem is that many of the variable annuity subacounts are actively managed and, just like their actively managed mutual fund counterparts, have proven to be cost-inefficient when compared to comparable index funds using the AMVR. While the annuity industry often argues about the need to preserve choices for plan participants, a cost-inefficient investment never has been, and never will be, considered a legally prudent investment choice.

Fixed Indexed Annuities

Dr. William Reichenstein is a chaired professor at Baylor University and a well-respected expert in the field of financial services. Dr. Reichenstein has authored several articles on the financial inefficiency of equity-indexed annuities, now known as fixed indexed annuities in order to avoid being classified as a security and subject to SEC regulation. Among his findings and conclusions:

Indexed annuities (IA) including equity indexed annuities (EIAs) are complex investment contracts. (citing features such as surrender penalties; an annuity’s “spread;” arbitrary restrictions on returns that owners can actually achieve, e.g., caps and participation rates, and ability to reset same on a regular basis and on such terms at the annuity issuer desires; market value adjusted options penalizing an annuity owner who withdraws money from an annuity before term, various interest crediting methods and potential interest forfeiture rules e.g., annual reset, point-to-point, or high water point; potential interest forfeiture rules; the issue of averaging and they type of averaging used.4

More important, because of their design, index annuities must underperform returns on similar risk portfolios of [Treasury bonds] and index funds. EIAs impose several risks that are not present in market-based investments including surrender fees and loss of return on funds withdrawn before the end of the term. This research suggests that salesmen have not satisfied and cannot satisfy SEC requirements that they perform due diligence to ensure that the indexed annuity provides competitive returns before selling them to any client.5

The interest credited on an EIA is based on the price index. So, the investor may get part of the price appreciation, but she does not receive any dividends associated with the underlying stock index. The return may be further reduced based on participation rate, spread, and cap rate. Moreover, the insurance firm almost always has the ability to adjust at its discretion the participation rate, spread, or cap rate at the beginning of each term.6

I was a securities compliance director when EIAs were first introduced. I remember sitting in a Monday sales meeting listening to the annuity wholesaler pitch EIAs and thinking, “no way. This is a lawsuit waiting to happen.” The regional manager, who was also a registered principal, leaned over and quietly said “we aren’t gonna approve these, are we?” My response – “I’m not.” I ran a tight ship.

As a result of the insurance lobby’s efforts, FIAs are technically categorized as insurance. This has allowed the annuity industry to mislead people into thinking that they can achieve the returns of the stock market or a stock market index via a FIA. So, investors immediately see the returns of a stock index, such as the S&P 500 index, and believe they can achieve similar results with FIAs. They quickly learn otherwise.

As the Wall Street Journal noted, this potential for “mind-boggling confusion” and potentially abusive marketing practices, such as selling EIAs/FIAs with long surrender periods to the elderly, resulted in many of the leading insurance firms refusing to offer EIAs/FIAs.9

As one insurance executive stated,

These products are so complicated that I think it’s a stretch to beleive that the agents much less the clients understand what they’ve got….The commissions are extreme. The surrender periods are too long. The complexity is way too high.10

The Mass Mutual Financial Group was so concerned about EIAs that they conducted an independent study comparing the performance of EIAs against the S&P 500 over a thirty period ending on December 2003. The results of the study?

Over the 30 years the equity-indexed annuity would have delivered just 5.8 percent a year, far below the 8.5 percent for the S&P 500 without dividends and the 12.2 percent for the S&P 500 with dividends reinvested. Indeed annuity investors would have been better off in super-safe Treasury bills which delivered 6.4 percent a year.11

And things have not changed. FIAs are structured in such a way as to continually ensure similar underperformance. First, as Reichenstein pointed out, FIAs investors do not receive any dividends paid out by the market index used in an FIA. True, that is because of the fact that the options that FIAs typically use in connection with FIAs do not provide dividends. The options are a pure market index price play based on the movement of the underlying market index. That said, dividends on the S&P 500 have historically provided approximately 40 percent of the S&P 500’s annual returns.

Second is the issue of the artificial and subjective restrictions on the amount of annual returns that FIA investors can realize. FIAs often impose restrictions such as “caps” on returns and/or “participation rates” in order to reduce their investment costs.

The impact of such caps and/or participation rates are exacerbated by an annuity issuer’s deduction of a yield spread, or “spread,” which is taken off the top of the FIA investor’s capped return, further reducing an FIA owner’s realized return. For example, assume an FIA imposes a 10 percent annual cap and a alleged spread of 2 percent, resulting in a realized end-return of only 8 percent. Other costs and fees may then be applied, further reducing the FIA owner’s realized return.

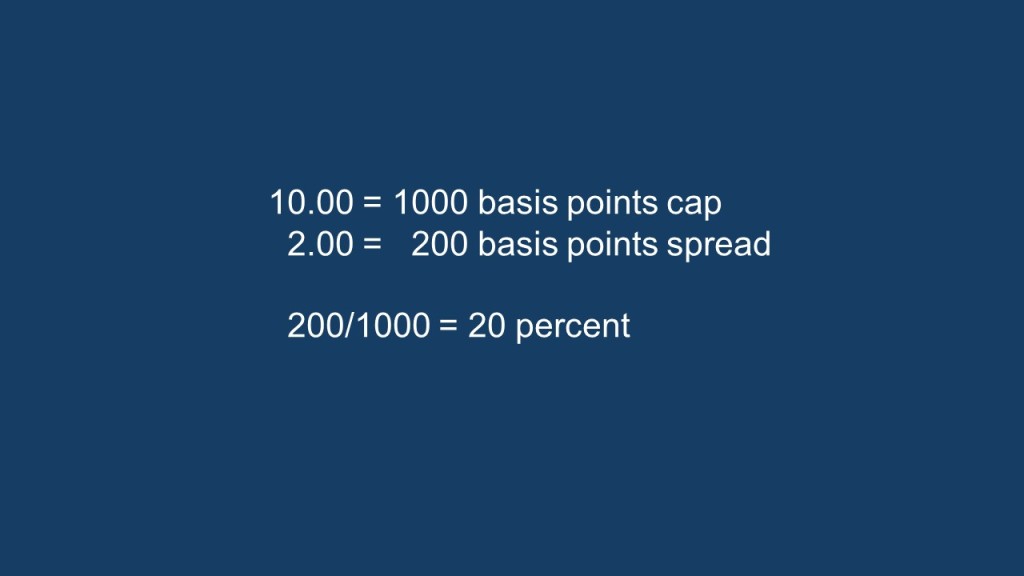

Insurance companies adamantly refuse to disclose the amount of spreads that they apply on annuities. For the sake of argument, let’s assume the insurance company claims that they apply a 2 percent spread. The financial services industry often refers to costs and fees in terms of “basis points” (bps). A basis point equals 1/100th of one percent (0.01). 100 bps equals one percent.

In our example, 2 percent would equal 200 bps. If the FIA had an annual cap of 10 percent 1000 bps), then the FIA would suffer a 20 percent loss of return (200 bps divided by 1000 bps), not a 2 percent loss. I would not want to be the attorney trying to argue the fiduciary prudence of an investment whose fees/costs results in an investor suffering a loss or 20 percent of their realized return!

Sadly, weak state insurance departments allow this abuse to continue unchallenged. Plan sponsors that choose to include FIAs as an investment option within their plan can be assured that the DOL and the ERISA plaintiff’s bar will not allow such abusive practices to go unchallenged, as demonstrated by the DOL’s recently revised Retirement Security Rule.

Going Forward

Annuity advocates often get frustrated with me because I refuse to argue the technical aspects of annuities. I simply reference the fact that neither ERISA nor fiduciary law requires that annuities, nor any other specific type of investment, be offered within a pension plan. Annuity advocates similarly refuse to acknowledge or address the legitimate fiduciary liability risks inherent in the current versions of most annuities.

I developed a simple fiduciary risk management process for my fiduciary clients, Keep It Simple & Smart (KISS). The system consists of three simple questions. My clients often remark that the KISS sytem is not not only simple and effective, but is further proof that simplicity is the new sophistication. Since it is based on ERISA and the Restatement (Third) of Trusts, I expect our 100 percent compliance record to remain unblemished if followed.

Whenever I am contacted by a client asking about the inclusion of an annuity in their plan, my response is simple and direct – “There is no legal requirement to offer annuities within a plan. So, why go there and expose yourself to the risk of unnecessary fiduciary liability. If employees want to buy an annuity, let them do so outside of the plan. Don’t go there.”

I would advise all plan sponsors and other investment fiduciaries to consider that same advice. Smart people do not expose themselves to unnecessary risk and liability.

Notes

1. Jeremy Babener, “Structured Settlements and Single-Claimant Qualified Settlement Funds: Regfulating in Accordance With Structured Settlement History,” New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy, Vol . 13, 1. (March 2010)

2. 29 U.S.C. § 1104(a).

3. Hughes v. Northwestern University, 142 S. Ct. 737, 211 L. Ed. 2d 558 (2022)

4. 29 C.F.R. § 2550.404(a).

5. Donovan v. Cunningham, 716 F.2d 1455, 1467 (5th Cir. 1983).

6. Reichenstein, W., “Financial analysis of equity indexed annuities.” Financial Services Review, 18, 291-311, 291 (2009); Reichenstein, W., “Can annuities offer competitive returns?” Journal of Financial Planning, 24, 36 (August 2011) (Reichenstein)

7. Katt, P., “The Good, Bad, and Ugly of Annuities,” AAII Journal, 34-39. (November 2006)

8. Milevsky, M. & Posner, S., “The Titanic Option: Valuation of the Guaranteed Minimum Death Benefit in Variable Annuities and Mutual Funds,” Journal of Risk and Insurance, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2009), 91-126, 92.

9. Jonathan Clements, “Why Big Issuers Are Staying Away From This Year’s Hottest Investment Products,” Wall Street Journal, December 14, 2005, D1. (Clements)

10. Clements.

11. Clements.

Copyright InvestSense, LLC 2024. All rights reserved.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is neither designed nor intended to provide legal, investment, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If legal, investment, or other professional assistance is needed, the services of an attorney or other professional advisor should be sought.

You must be logged in to post a comment.